Independent media is essential in

having informed educated and non-bias citizens. However, according to the World

Association of Newspapers and News Publishers, the presence of independent

media is severely lacking in Arabian countries. Additionally, independent media

can only be fostered in an environment in which journalists are able to carry

out their duties without fear of violence. Without this environment, media

tends to be one sided without a comprehensive look at the political

environment. The independent and opposition media has been largely oppressed

throughout the Middle Eastern world in the past few centuries by government

forces. With the limited amount of independent media in Egypt, Tunisia and

Syria, social media, state run media and opposition media represent a large

portion of reporting on events during the Arab Spring.

Since the rule of the Ottoman Empire,

the Middle East and Northern Africa have had limited freedom of press. Once the

empire had ceased to exist, the press became an instrument in the fight for

national independence from colonial powers. However, after power was ceased back by

revolutionaries in the 1950’s, independent and opposition press were

forbidden in most countries. Out of the three countries in focus, the only country

to continue to allow independent and opposition media was Tunisia (Essoulami). This does not

mean freedom of press though, as it was only tolerated and was subject to

censorship and criticism in order to protect “public order”. Much of this

changed in the 1990’s when “satellite television in the Arabic language took

the region by storm … boosting access to information, breaking taboos, and bringing

the Arab world closer together …”(Noueihed, 46). Not only did this bring the

Arab world together culturally, it allowed them to share their human condition

and stories with others that are under similar oppression. However, freedom of

press is still nowhere near guaranteed, “[J]ournalists there know they must

censor themselves on pain of serious consequences.”(Swafield).

Until 1996, with the creation of

the Al-Jazeera news network, citizens that wanted to watch professional news instead

of entertainment or state run propaganda bulletins had to turn to English or

French satellite broadcasts (Noueihed, 47). Through controversial political

talk shows and news reporting, Al-Jazeera played a significant role in eroding

the propaganda system that dictators had worked so hard to create. With the US

led invasion of Iraq, Al-Jazeera was the only foreign news network with a correspondent

in the country. By showing raw footage of airstrikes and messages from Osama

bin Laden, the network earned the name “Jihad TV” in the U.S. (Noueihad, 49).

However this correspondence only gave the channel more credibility in the

Middle East and Northern Africa. “A 2010 opinion poll found that 85 percent of

Arabs relied on the television for their news, and that 75 percent listed

Al-Jazeera as either their first or second choice for international news.”

(Nouihad, 50).

Although freedom of press is guaranteed in the Constitution of Tunisia, journalists were not comfortable before and during the Arab Spring. This

is due to the regime’s intimidation and oppression of journalists; According to Bruce

Swaffield, since 2008 organizations “have cited more than 30 separate incidents

involving the media. From censorship to arrests to imprisonment …” (Swffield).

This was allowed to happen by the international community because much of the

intimidation was done under the guise of a reporter committing a separate crime

such as

theft. Due to this, much of the information that was disseminated during

the uprising was through twitter and blogging services. Although bloggers were

still a target for the government, it was more difficult to identify the source. The

state of independent media has improved within Tunisia since the uprisings as

bloggers can express their political view without fear of attack by the secret police.

Egypt has been better off than most

Middle Eastern and Northern African countries in terms of freedom of press and amount

of independent media. Since the U.S. led invasion of Iraq, Mubarak was

pressured to put in place democratic reforms, this included the implementation

of opposition and independent newspapers. However, Mubarak’s state run Al-Ahram

still produced plenty of propaganda; and independent and opposition journalists

were still intimidated by security forces and his regime put in significant

effort to shut down the internet, mobile phone networks and Al-Jazeera’s Egypt

bureau, to control access to information within the country during uprisings. Due to this, “most

of the reliable news about the 18-day revolt, in fact, came from social media

networks, international news sources, and independent and opposition Egyptian

press outlets…” (Elmasry).

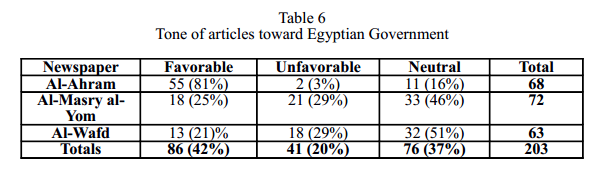

Although there is no casualty proven by government ownership, opposition party

ownership and independent ownership of new sources, the statistics presented

support the expectation that ownership structures and political loyalties constitute

a major structural influence on news production (Elmasry).

From this overview it is clear that

the state of independent media in the Middle East and Northern Africa must

change. There is barely any freedom of press within most of these nations and

the little that is presented is controlled tightly by security forces and

regimes by intimidation and the need to ‘self-censor’. The only major

independent news source comes from the use of satellite television and internet

blogging sites. Furthermore, “Research has

shown that, on the whole, Arab media tend to operate within censorial cultures,

with authoritarianism and social responsibility overriding liberalism as media

norms (Hafez 2002; Mellor 2005)” (Elmasry). Independent media is

becoming non-existent as “The media are being divided into two parts, one loyal

to the government, the other to the opposition” (Kilman). In order to counter

this trend, people must advocate for laws that ensure Freedom of Press within

the nations and support the development of independent satellite news channels

that broadcast in Arabic within the area.

Works Cited

Elmasry, Mohamad Hamas. "Journalism With Restraint: A Comparative Content Analysis Of Independent, Government, And Opposition Newspapers In Pre-Revolution Egypt." Journal Of Middle East Media 8.1 (2012): 1-34. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Essoulami, Said. "The Arab Press: Historical Background." Al-bab. N.p., 7 Jan. 2006. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Griffen, Scott. "Restrictions on Independent Media in Syria Must End, Says IPI." International Press Institute. N.p., 6 Feb. 2012. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Halverson, Jeffry R., Scott W. Ruston, and Angela Trethewey. "Mediated Martyrs of the Arab Spring: New Media, Civil Religion, and Narrative in Tunisia and Egypt." Journal of Communication 63.2 (2013): 312-32. Academic Search Complete. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Jouan, Virginie. "Long Road Ahead for Tunisia's Media." International Media Support. N.p., 11 Jan. 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Kilman, Larry. "Arab World Needs Access to Independent Media." World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers. N.p., 25 Nov. 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Krajeski, Jenna. "The Death of Egypt Independent." The New Yorker. Condé Nast, 30 Apr. 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

"Media Sustainability Index - Middle East & North Africa." IREX. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Morabito, Andrea. "The Trouble With Syria." Broadcasting & Cable142.9 (2012): 10. Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 13 Apr. 2014

Noueihed, Lin, and Alex Warren. The Battle for the Arab Spring: Revolution, Counter-revolution and the Making of a New Era. New Haven: Yale UP, 2012. Print.

Reventlow, Andreas. "Making Sense of Egypt's News." International Media Support. N.p., 29 June 2013. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Swaffield, Bruce C. "The Story Tourists Never See in Tunisia." Quill 96.9 (2008): 37. Academic Search Complete. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

Swaffield, Bruce. "Whims Often Lead To Syrian Journalists' Woes." Quill 95.4 (2007): 38.Communication & Mass Media Complete. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

"World Press Freedom Index 2014." Reporters Without Borders. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2014.

No comments:

Post a Comment